From Philly and suburbs of Pa. in South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Tell us!

Few things sit as central to the intersection of science, politics, health and culture as the school lunch.

In the early 20th century, most states in the US had some form of compulsory education: children had to go to school. If the government can force children to go to school, should it also feed them?

If so, what?

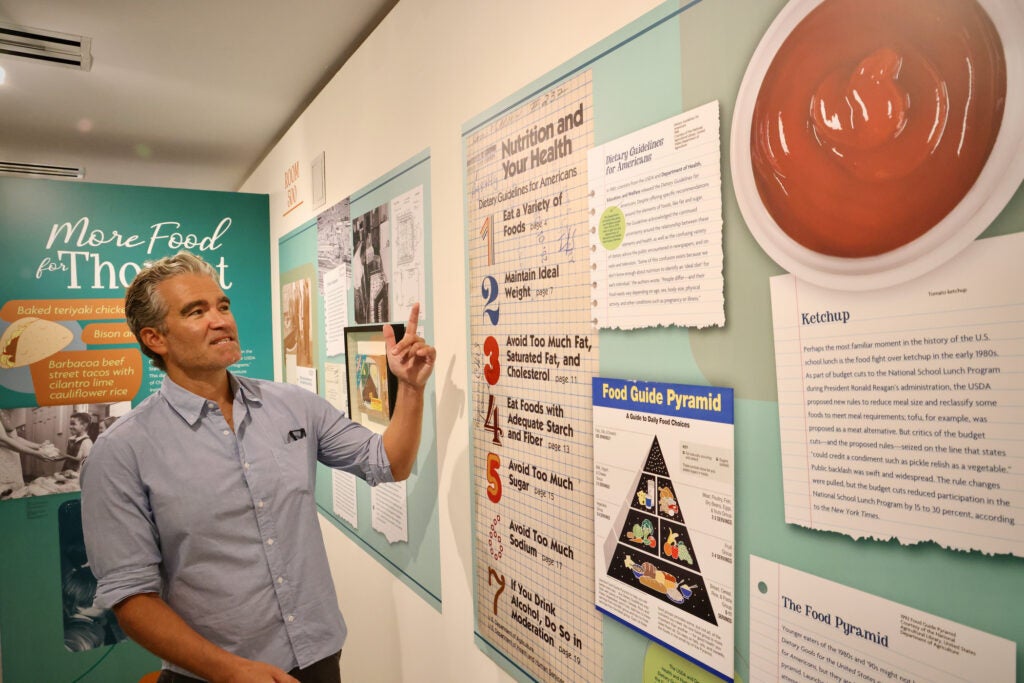

“The history of school lunch is a history of conflict,” said Jesse Smith, director of curatorial affairs at the History of Science Institute in Old City. “People have always argued during lunch at school, until now.”

Smith curated “Lunchtime: The Story of Science on the Lunch Tray.” Just days before it opened, school lunches were back in the news. A minor political tussle emerged in Washington as lawmakers clashed over a bill that would provide free meals universally to all students, regardless of income eligibility.

The universal free meals bill is tied to a USDA rule that participating schools must have anti-discrimination policies, consistent with President Biden’s executive order on racial equality and LGBTQ. Some Republican members of Congress oppose the rule.

“The Biden administration’s poisonous transgender agenda is calling into question children’s school lunch funding,” said Roger Marshall, a Republican senator from Kansas, as reported by The Hill newspaper.

In Philadelphia, free universal lunches have been in place in the school district for the past 10 years under the USDA’s Community Eligibility Program, which reimburses the cost of meals for all students, regardless of income, in schools in high-poverty areas. .

Statewide, all students have access to universal breakfasts, while free lunch in most of Pennsylvania is tied to income eligibility.

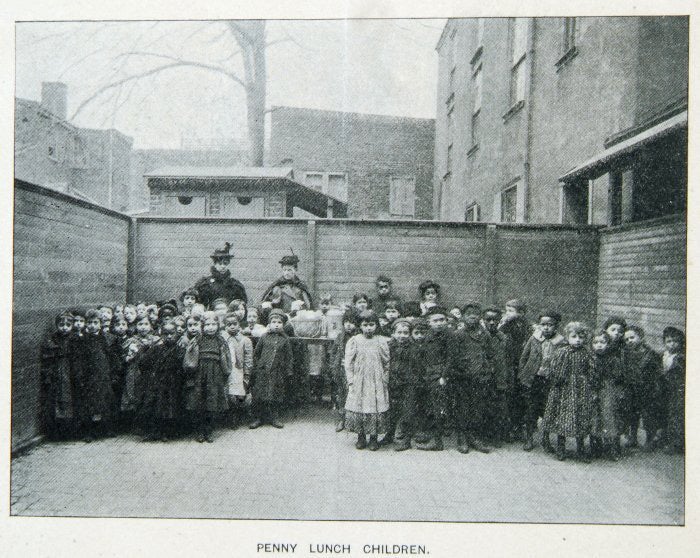

Historically, Philadelphia has been at the forefront of school nutrition. In 1894, along with Boston, the two cities were the first to offer meals to students. In Philadelphia, the program was in only a handful of schools and was run by a community service organization, the Starr Center Association.

Students paid for a “penny lunch” with a prepaid one-cent token, an example of which is displayed at lunchtime. In 1910, the Philadelphia school district adopted the Starr lunch program and expanded it to all of the city’s public schools.

Lunchtime, the exhibit, is designed with a mid-century modern pop aesthetic — all pastel colors and bubbly graphics — circa 1946 when President Harry Truman signed the National School Lunch Act, providing free or reduced-cost lunches. for qualified students.

However, 1946 is the middle of this story. It began in the late 19th century, when populations were moving from agricultural to urban areas for factory work. Business tycoons looking for ways to keep the workforce productive looked to new research in nutrition science to determine what exactly is needed to sustain a worker.

“Fuel, in the broadest sense, is critical to what we know as the Industrial Revolution,” Smith said. “Things like coal, but also the food that’s feeding the individuals that work in these factories.”

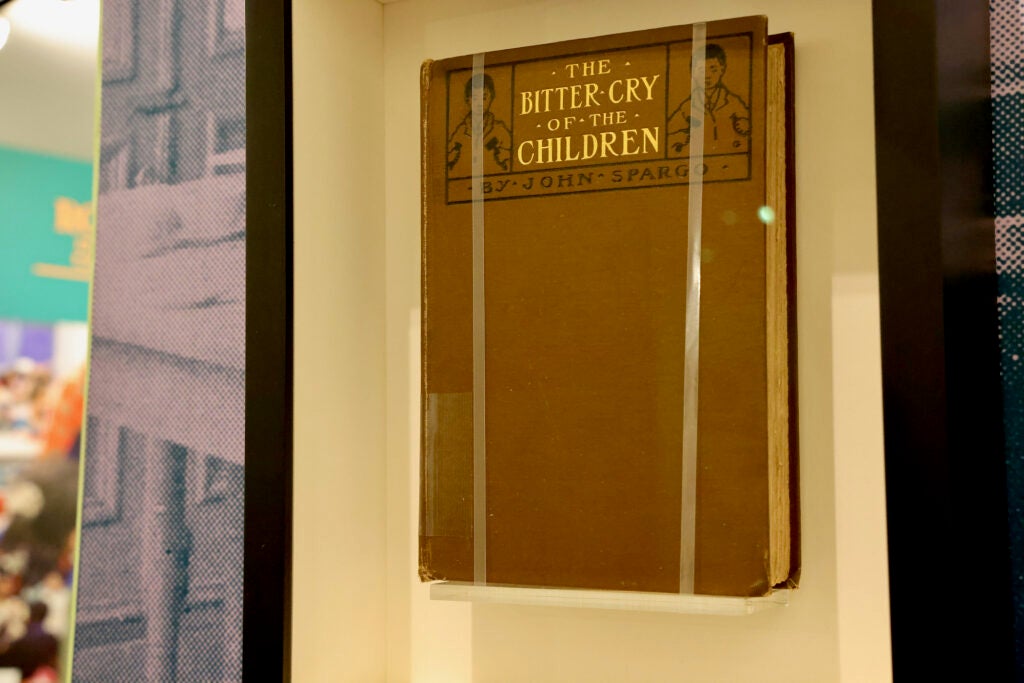

But if children are left to make their own dietary decisions, these choices are rarely wise. In 1907, journalist John Spago published a chilling book about the lives of children in factories and schools, The Bitter Call of Children. He saw children buying themselves a lunch of ice cream and cigarettes.

At the turn of the century, most schools did not offer any kind of lunch. Children had to bring their own from home or buy food from nearby shops and street carts. Lunchtime shows that in 1910, Columbia Teachers College enrolled children in school eating frankfurters and rolls, bananas and licorice, Swiss cheese bread and frosting.

“We wanted to highlight some of the meals that students would have eaten at that time,” Smith said. “I think today, we have a sense of what iconic school lunches might be – things like fish sticks and Salisbury steak – but at other times, it might have been rice soufflés with liver and cheese.”

The first dietary recommendations from the USDA came in 1916, suggesting that children ages 3-6 eat a piece of lamb, chopped spinach, rice with milk and sugar, bread and butter, and baked potatoes.

During this period, states passed compulsory education laws; Mississippi was the last to do so in 1918. However, few schools offered lunch, and those that did were not accountable to USDA or other guidelines.

Modern school lunch logistics were formally developed in 1920 by Philadelphia School District lunch czar Emma Smedley in her book The School Lunch: Its Organization and Management in Philadelphia.

“This was a manual that explained what she was doing in Philadelphia: menu planning, hiring, organizing storage spaces,” Smith said. “Things we might take for granted today, but it was all being developed from scratch back then.”

By the 1930s and 40s, global forces began to shape school lunches. Advances in agricultural science, especially new synthetic fertilizers, were generating unprecedented amounts of food.

The National Trash Association was so proud of its accomplishments that it produced a truly strange piece of pop culture in 1951: a comic book called “The Hunger Games” featuring happy, well-fed children going on adventures with an anthropomorphized bag of fertilizer. .

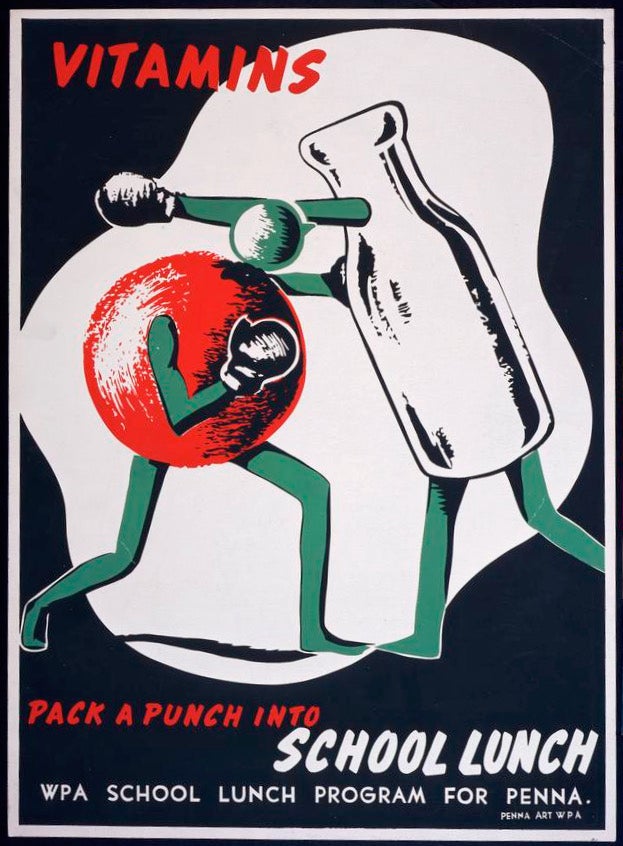

Crops were thriving, but fewer people could afford them when the Great Depression hit in 1929. The US government bought up surplus agricultural produce and donated it to schools to keep farmers afloat. The Works Progress Administration employed thousands of people to prepare and serve lunches in schools across the country. Thus the free lunch was born.

World War II created an urgency for nutrition standards. Six months before the US entered the war, President Franklin Roosevelt called a National Defense Nutrition Conference: “The fighting men of our armed forces, the workers in industry, the families of those workers, every man and woman in America, must have nutritious food.” he wrote.

(Courtesy Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia)